The only path to transmit knowledge

Explaining the STEM-humanities divide from the STEM point of view.

1. Definition, Proposition, and Verification

Continental philosophers and scientists haven’t always gotten along. Famously, in 1996 a physicist -Alan Sokal- submitted a deliberately nonsensical and jargon-filled article to the cultural studies journal "Social Text." The article was intended as a critique of postmodernist academic writing and the perceived lack of rigor in certain disciplines. The manuscript was accepted by the editors and published, sparking a significant controversy and discussions about the standards of academic journals and the relationship between science and postmodernism. But it is not just this incident that marks a divide between the humanities and the sciences; discussions with individuals in STEM departments often reveal perceptions that philosophers are overly verbose or incomprehensible, while those in the humanities often think that scientists are rigid and philosophically naive. Why is there this gap between the two camps?

A piece of the puzzle might be this: researchers in STEM, whether consciously or unconsciously, often believe that there's only a singular path to formalize knowledge. Let me elaborate. Mathematical knowledge, taught to all STEM students, is formalized by giving clear definitions, with which one can state propositions that can then be verified. While this framework to formalize knowledge may initially appear limited to the mathematical domain, it is surprisingly encompassing.

Consider the knowledge of how to bake an apple pie, which is formalized as a recipe. A recipe is a structured set of instructions that, when followed correctly, should result in an apple pie. In a mathematical sense, the recipe can be viewed as a proposition: if all the specified conditions (assumptions) are met, the desired outcome (the pie) will be achieved. Successfully baking the pie requires not only following the steps but also understanding what each instruction entails, ensuring that all assumptions—such as having the correct ingredients, tools, and techniques—are satisfied.

To properly understand the instructions, one must be familiar with the definitions of the words used in the recipe; for instance, 'add 100 grams of sugar' is comprehensible when one understands the grammatical rules of the English language and the meaning of each word in the sentence.

To then know if the recipe represents actual knowledge of how to bake an apple pie (if it’s true) one can follow all the instructions in the recipe and see if a tasty apple pie is produced, verifying the proposition. 1

Now take the ability to fix an electrical grid or change the wheel of a car, these too can be formalized by a set of instructions that if performed correctly will provide the desired result. In these cases, there might be troubles in understanding all the definitions, for instance, if someone says “Place the wheel chock behind the tier” one might answer “What the hell is a wheel chock?” and the propositions could be very long and complex but the overarching structure (definitions, proposition, verification) remains the same. This paradigm appears to hold true all the way up to theoretical physics: one provides clear definitions of the quantities of interest, states hypotheses or physical laws, and then inductively checks whether the hypotheses hold true under the given assumptions—if he wants to test their veracity. 2

2. Enter Philosophy

At this point, the philosophers join the conversation and—correctly—point out that it may actually be technically impossible to give clear definitions (some fuzziness always remains) and that we don’t really understand what rules govern the inductive process of verification (thanks Hume). Nevertheless the structure we have described for how we empirically transmit knowledge remains unchanged. It’s not that the objections raised by philosophers don’t have merit, it’s that they don’t alter the empirical reality we seem to operate within; the paradigm of defining terms, stating propositions, and verifying them. Despite our inability to precisely explain its workings, we have a productive pathway to formalize and share knowledge.

Is this the only way we can go about transmitting knowledge?

I suspect that individuals in STEM disciplines, whether consciously or unconsciously, tend to answer yes to this question. Perhaps they are correct, given that there is little reason to believe our evolutionary history would equip us with 'other ways of transmitting knowledge.' It would seem like a costly redundancy that would be seldom employed. 3

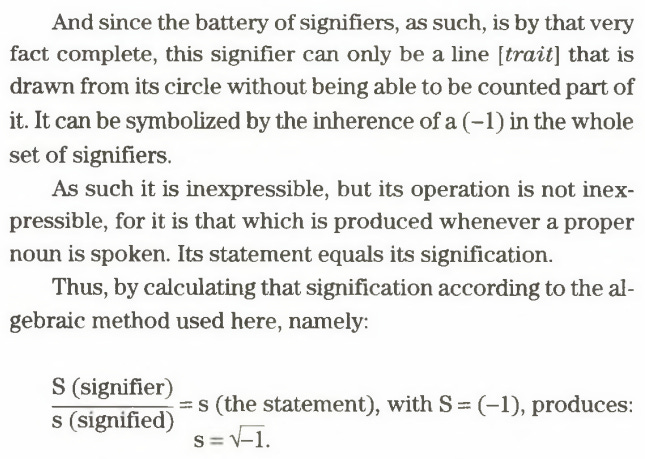

So when scientists, for instance, read the following passage by Jacques Lacan

their alarm bells go off; What is the meaning of the equality sign? What is the definition of what appears to be a division line? How do we multiply numbers by words? The first step of the transmission of knowledge paradigm is being violated: definitions are not being clarified.

Without precise definitions, we are faced with an incalculable number of reasonable interpretations. Perhaps Lacan is suggesting that combining the statement and the signified yields the signified, or maybe he is asserting that the signifier, in some manner, dominates the signified. Another interpretation could be that obtaining the signifier from the statement and the signified requires extending their category, akin to how imaginary numbers extend the real numbers.4 Or perhaps the best interpretation of what Lacan meant is this one (pag 155).

Among these interpretations, there are undoubtedly some—often more than one—that make the writings appear perfectly coherent. However, it's unclear which interpretation aligns with what Lacan had in mind, and the rationale for all the additional effort required to (maybe) comprehend the knowledge Lacan is purportedly trying to transmit remains mysterious. The same can be said for countless other excerpts of continental philosophy.

Surely if one wants to depart from—the tried and tested—paradigm to communicate knowledge effectively there should be a compelling motivation to do so. The difficulty philosophers warned us about in providing precise definitions is exactly why one must invest effort in making them as clear as possible. The solution is not to abandon the endeavor altogether but to redouble efforts, aiming to minimize the range of reasonable understandings of the text. Perhaps some thinkers are inclined towards an alternative way of sharing knowledge or have discovered a novel method, in which case, explaining its functioning would greatly benefit our collective understanding. Otherwise, the ambiguity in definitions and the use of evocative language seem to introduce unnecessary complications.

At this juncture, one might contemplate a question or two: Why would some thinkers write in highly complicated sentences without attempting to clarify their definitions? After all, if their text simply adds complexity to the already challenging task of transmitting the knowledge of a philosophical or psychoanalytical theory, what motivates such an approach?

3. Possible Explanations

Philosophy is divided in four main branches (logic, ethics, epistemology, metaphysics) each harder to study than the next, philosophers are up against questions concerning the fundamental nature of reality, this endeavor is so onerous that a folk assumption is that the term metaphysics means "transcending physics". Philosophers don’t have much data to tackle problems concerning the fundamental nature of reality so they are left with reasoned arguments and intuitions, making conclusive answers rather elusive. Unlike physics or mathematics, where success hinges on being demonstrably correct, a philosopher's impact is harder to gauge by simply being "right" or "wrong." Thus a surrogate measure of success creeps in; how influential a philosopher manages to be.

To influence and persuade people it seems like there are generally two routes, one is that of rhetoric and sophistry, the other is that of substance and reason. For enthusiasts of dual process theory, the former resonates with the instinctual System 1 processes, whereas the latter engages the reflective System 2. Under these paradigmatic lens we can consider potential reasons (some more valid than others) for the opaque writings of philosophers.

a. Edutainment

Writing clearly might be the most effective way to convey information, but it can be rather dull—some might say boring. So, if one can make their writing more engaging, even at the expense of sacrificing some clarity, it may encourage people to read with more passion. This principle underlies the concept of edutainment. But there is a risk in having an exceedingly charming pen; one might convince the reader through the power of his wit and not by appeal to their rational faculties.

b. Puzzle Passion

Some people find pleasure in solving puzzles. Leaving an interpretative line in a text that, if found, suddenly makes one understand what the author was going for can be a powerful and pleasurable experience for the reader, sometimes so much so that one will confuse it with one of epistemic value, in a weird rendition of the sunk cost fallacy.5

c. Inspiration

An ambiguous text might inspire the reader. When a text opens itself up to interpretation, there is a chance that it might generate novel ideas in other individuals. Although this remains true (perhaps truer) for texts that don’t allow for myriads of interpretations, but let’s be charitable; cryptic musings might not be completely valueless.

d. Self-Serving Sophistry

Lastly (although surely I am missing other reasons in this short list), one might choose to write nebulously because it provides an effortless means to feign profundity. It's a convenient way to generate deepities. This “style” of writing should correctly be identified as a form of academic malpractice.6

Whatever the reason, it would be fitting to clarify the author's intentions upfront, especially when a text presents itself not as a work of literature but as a philosophical or psychoanalytical investigation. Otherwise, individuals accustomed to the highly successful definition, proposition, verification approach to transmitting knowledge might be inclined to suspect foul play.

Yes, in the case of math, the proof is deductive while the way we are testing whether a recipe is true is inductive. Nonetheless, the structure of how we formalize knowledge remains the same. Also, deduction can be seen as a specific kind of induction (one where there is 100% certainty) so the two concepts are nested and less dissimilar than one might initially presume.

Even the early transmission of language can be framed under this paradigm. Children are taught, through repetition, the definitions of words and some grammatical rules. Sentences can be viewed as propositions that can be verified for correctness through the behavior of the interlocutor. For example, if I say 'pass me the salt' and my interlocutor does pass me the salt, I have verified the correctness of my proposition.

Incidentally, there might also be only a single method for acquiring knowledge that is observed in children and which remains true all the way up to the best scientific minds and the most powerful artificial intelligences.

We are assuming that Lacan clearly defined these terms previously.

Some artistic creations make use of this stratagem to good effect and personally I delight in it. I remember being pleasantly surprised when I discovered, two or three years after my first viewing, that the main theme of Pulp Fiction was coincidence and its butterfly effect on human life. This also explains my love for Kubrick.

We should not be scandalized by the prospect of academic malpractice (beyond plagiarism) occurring even in the humanities. After all the human mind is ingenious and imaginative so academic malpractice takes on various forms in all fields of inquiry: in statistics, medicine and the social sciences, it’s p-hacking and data torture; in computer science, tweaking hyperparameters in a neural network is passed off as a way to "beat" the state-of-the-art loss; in physics, people have forged entire datasets, and even in mathematics, leaving out gaps in your work can lead to controversies *cough* Mochizuki *cough*. It would be peculiar if the humanities, which spans fields where assessing the validity of the work is often even more challenging, only attracted paragons of virtue.

> and the propositions could be very long and complex but the overarching structure (definitions, proposition, verification) remains the same.

You actually need more than scientific and mathematical methodology for that, you need philosophical methodology (e.g. how propositions relate to one another through a chain of (often modal) logic), although this is not really obvious to us until the day we run into someone who interprets the chain differently.

> Even the early transmission of language can be framed under this paradigm. Children are taught, through repetition, the definitions of words and some grammatical rules. Sentences can be viewed as propositions that can be verified for correctness through the behavior of the interlocutor. For example, if I say 'pass me the salt' and my interlocutor does pass me the salt, I have verified the correctness of my proposition.

Not really, if I yell at my cat "don't walk on the table!" the cat sprints off the table. I might interpret that as verification through behavior, but my cat seems to think I mean "don't walk on the table while humans are present, otherwise walk all over it"

Also, not all of language is propositions. When I say "pass me the salt" that's actually a command, and "can you pass me the salt?" is a question. You need a bit more to interpret that, which bring me to...

> While this framework to formalize knowledge may initially appear limited to the mathematical domain, it is surprisingly encompassing.

But this is not the only formalization. I already talked about philosophical formalizations (logic), but there's another discipline that has it's own suite of formalizations that may help us here: linguistics, with its fields of theoretical and formal linguistics. Is linguistics part of the humanities or of science? That depends on your definition. I'm not going to pretend to be an expert, but at the very least it's another lens through which we can formalize things.

Hi, Im here because i cant coment on ur youtube video about Latour.

I think many of your, u and people on the coments, "Latour points" are not correct.

Latour doenst pursue any "social explanation" of sci practice, he and his colegues develop a "social" science aproach to follow and register closely sci and tech practices and enterpreises, he in fact reject "social explanations" for sci and tech, and almost for any issue (he rejects structuralism).

I think is a bit dangerous misunderstand his work as long as, i think, provide us for a powerfull tool taht will help us transform our societies in the age of climete change