Over the past few years I've been using a mental model regarding politics that I like to think of as a form of Dual Process Politics. I’ve mentioned it before—once in a video, and once in what I still think is one of my best articles. But I’ve never actually written about it—so here I am.

I find the framework useful (that’s why I’m presenting it to you, my beautiful readers), but I also think it has its weaknesses. I’d like to briefly explain both trying to maximize the signal to noise ratio. To do so I must give the obligatory quick refresher on Dual Process Theory. If you’re already in the know, feel free to skip ahead to Section 2.

1. Dual Process Theory

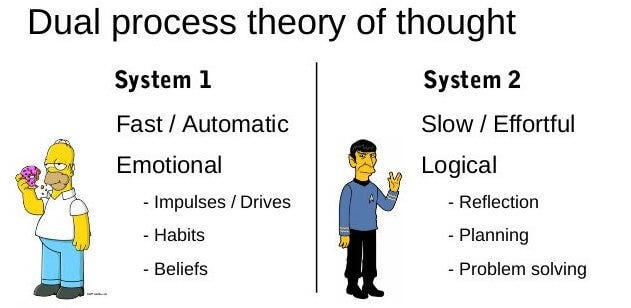

Kahneman and Tversky, two of the most influential figures in cognitive science, proposed that the human mind operates using two distinct modes of thinking.

The first is fast, intuitive, emotional, and automatic. It’s what allows you to recognize a friend’s face instantly, dodge a flying object before you even register it, or reflexively answer “four!” when asked what two plus two is. They called it System 1—the brain’s rapid-response mechanism, fine-tuned for snap judgments and instinctive decisions. It excels at solving the kinds of problems our ancestors needed to handle immediately, like “Is that a tiger?” or “Should I start running?” It also governs habits, internalizing heuristics so effectively that certain responses become second nature.

But while System 1 is fast and efficient, it’s not always accurate. It relies on mental shortcuts that usually work—but that can lead to systematic biases and misjudgments. It’s the reason you might instinctively assume a rustling bush hides a predator when it’s just the wind. If you wanted an unrequested AI analogy, System 1 is like one of those GPTs that spits out answers instantly without pausing to think. It prioritizes speed and efficiency over accuracy.

Then there’s System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and effortful. This is the part of your mind that carefully weighs arguments, grinds through a tough math problem, or painstakingly tries (and fails) to compose a great sonata. Unlike System 1, it doesn’t just react—it stops, thinks, and evaluates, making it more cognitively costly but also more accurate.

If System 1 is a reflexive AI spitting out responses instantly, System 2 is the version that takes a moment to “think” before answering, it tends to be more accurate and thus more effective for logical reasoning, coding and complex math problems.

It goes without saying that both systems are crucial for survival and flourishing. But evolution probably gave us System 1 first—because forming quick mental models of our environment and making snap judgments is more immediately useful for survival than, say, solving partial differential equations.

Before proceeding, a quick disclaimer: while Dual Process Theory is highly influential, it’s not uncontested as a framework for psychological decision-making. Cognitive science has other models too to decide what is going on up there (although they can somewhat be seen as refinements of Dual Process Theory rather than outright alternatives). For a good overview see this Substack article.

2. Dual Process Politics

My very straightforward, almost trivial intuition is this: since Dual Process Theory describes human cognition in general—indeed we see it at work across various domains of thought, from physical and mathematical reasoning to visual perception, spatial awareness, and social interactions—it seems natural that the same cognitive tradeoff between efficiency and accuracy would extend into the realm of political thought too.

If we accept this extension, we should expect a predictable, material divide, between those who primarily engage in politics using the slow, analytical, deliberative mode of thinking, and those who, whether due to time constraints, lack of inclination, or simple habit, rely more on intuitive, heuristic-driven judgments.

The implications could be major, are there some systematic biases in political thought too? Could certain political ideologies naturally appeal more to one cognitive style than the other? Let’s try to describe how things might work.

3. System 1 Politics

As we said, System 1 is all about efficiency. It’s the brain’s way of quickly making sense of the world without getting bogged down in complexity. So what would we expect could happen when applying it to politics?

a. In Practice

In practice, we might expect that the sheer cognitive cost of maintaining an accurate mental model of political reality—complete with shifting factions, ideological subtleties, and policy trade-offs—is extremely high. System 1, favoring efficiency, should tend to collapse things down for simplicity turning complex issues into black-and-white narratives.

After all tracking nuances within an opposing camp is mentally expensive and offers little immediate value. As a result, opposing viewpoints could tend to blur into a single, undifferentiated blob: the outgroup or, even better, the enemy.

We might also expect that those relying too heavily on System 1 thinking will be extremely confident in their positions while struggling to accurately explain opposing views—or, if they try, they’ll produce a wildly distorted strawman. Rather than engaging with alternative perspectives in honest debate, they’ll assume their opponents are either stupid or outright evil and move on with their day, saving valuable thinking tokens.

Dogmas and slogans will help make things more efficient, as they are useful thought-terminators and metacognition is expensive. If you have to choose between “this is a complicated policy issue with many trade-offs” and “we just need to get rid of the bad people,” System 1 will take the latter every time. Of course in a simple world, problems should be easy to fix. The only reason they haven’t been fixed is because of evil, corrupt, or incompetent people. If only our side got into power, everything would be better.

When it comes to voting, our System 1 shouldn’t be very interested in white papers or policy details. It prefers charisma, vibes, and emotional resonance. A leader who feels right over one who merely is right.

Moreover our System 1 might also find conspiracy theories particularly appealing. Conspiracies often offer simple, repeatable narratives that explain a complicated world in one fell swoop. And, along the same lines, we might expect a pull toward anti-scientific beliefs—after all, science is hard. It produces counterintuitive results, demands patience, doubt, and a tolerance for ambiguity—none of which align well with a first-instinct-driven approach to the world.

b. Ideologically

What to expect at an ideological level? This part is trickier because, in a sense, many political concepts can be seen as ways of flattening complexity. But let’s try to proceed anyway.

Racial or Sexual essentialism seem like great System 1 shortcuts. Instead of dealing with the tangled web of biology, culture, history, and individual variation, they reduces everything to X group good, Y group bad. The same might go for fundamentalist ideologies, which further minimize cognitive effort by offering a prepackaged script—just follow the rules in the (sacred) book that has all the answers.

More broadly, any narrative that frames politics as a straightforward battle between the good, honest people and the clear villains is likely to resonate deeply with System 1. And at a purely political level, one might suspect that extreme ideologies often employ simplifying shortcuts, reducing political reality to an effortless setting with an obvious solution. See this academic article along with a previous Substack article of mine for some supporting evidence.

So, from the perspective of Dual Process Politics, it wouldn’t be a coincidence that the Nazis were steeped in conspiratorial thinking, that both Stalin and Hitler were antisemitic, or that oppressive regimes want to terminate free thought (compute spent on thinking about society). Totalitarianism is the ultimate dimensionality reduction technique, the logical endpoint of letting System 1 thinking dominate.

4. System 2 Politics

Our System 2 will want to do much the opposite of its bizarro twin: approach politics more methodically, build arguments from first principles, tolerate uncertainty, and adjust beliefs in response to new evidence or valid criticism.

We would expect System 2 thinkers to be more familiar with opposing arguments, capable of steelmanning rather than resorting to strawmen. Not only would they better grasp the difficulty of predicting policy outcomes due to their higher resolution map of the world, but they’d also be more likely to understand the structure of arguments themselves—their syllogistic underpinnings and their place within an argument map. Rather than reacting to ideas viscerally, System 2 thinkers might reason from premises, assessing whether an argument is actually sound and valid before deciding whether it feels right. On average, they might be more uncertain in their conclusions, recognizing just how complex and unpredictable socio-economic systems can be.

They’d probably also make a greater effort to seek reliable information, avoiding fake news and simplistic narratives. Instead of fully committing to one rigid worldview, they’d be more inclined to pick and choose good ideas from different political traditions, favoring pragmatism over ideological purity.

5. Broader Implications

If Dual Process Politics were approximately true, it could help explain why certain patterns in politics seem to repeat themselves.

For instance, in practice, most people don’t have the time, energy, or inclination to devote significant mental compute to politics. This means that successful politicians will naturally tailor their messages toward System 1 thinking, relying on slogans, inspiring rhetoric, and simple, easy-to-digest ideas rather than detailed policy discussions.

Or consider why political debates rarely change minds in the moment. This would be expected under Dual Process Politics because truly reconsidering a position requires cognitive effort—stopping to think, weighing arguments, and engaging System 2. Something that only happens when you take a shower at home afterwards.

An interesting thing to notice is that Dual Process Politics challenges the belief that if low-information voters were simply given more facts, they would make smarter political choices. The issue isn’t just a lack of data—it’s that some people aren’t in the habit of expending compute for politics in the first place. Even when presented with high-quality information, if they default to System 1 processing, they won’t get a higher-resolution picture of reality.

If this is true, it raises concerns about the long-term trajectory of political thought in democratic societies even when no misinformation is present. Could the rise of short-form content—memes, soundbites, viral tweets—be actively training us toward System 1 thinking, making deep political reflection harder? If political discourse is increasingly optimized for engagement rather than nuance, we might need to ask: Are we fostering an environment conducive to System 2 political thought?

Then again, this is nothing new. Maybe there’s no less per-capita System 2 thinking about politics than there ever was. Either way, Dual Process Politics could raise some interesting sociological questions about how we engage with information and navigate political beliefs.

6. Uses

Personally, I’ve found this framework useful for sizing up people and ideas. It’s helpful to wonder if thoughts are more accurate or compute efficient. To give two examples, that will make people angry in a bypartisan manner, ideas like “All cops are bad” (perhaps expressed through calls to defund the police) or “All people of a certain race or religion are bad” appear like System 1 takes—emotionally charged, with a black-and-white resolution. Examples abound.

Another use I’ve found is through awareness, like most other people I know, I tend to be cognitively lazy. My brain doesn’t want to expend more mental energy than necessary to engage with the world, and that often leads me to default to System 1 politics. Sometimes, I will want to condemn forever an entire group of people because, frankly, I’ve had enough of their bullshit.

But the framework also acts as a good reminder that most people who disagree with you likely aren’t mustache-twirling villains—maybe they’ve just processed the same information differently. So then I go take a shower, reflect on the limitations of my brain, and—every so often—realize I wasn’t as correct as I thought I was. System 2 thinking is hard. I notice it when I try to solve a complex math problem, and I notice it even more in politics.

7. Caution Ahead

Even if Dual Process Politics provides a decent approximation of reality, the way I’ve described it might still be mistaken. For instance, one could argue that the status quo—not totalitarianism—is actually the most “unreflective” position, since accepting things as they are often requires little thought. And, to be honest, I could see his point.

There’s also a danger of misinterpreting what this framework tells us. For example, we shouldn’t assume that radical ideas are wrong by default. Some System 2 superusers end up with radical conclusions (I might have some of my own). The key is in understanding whether the idea is the result of correct serious reflection or not.

Another temptation to avoid—one I sometimes catch myself slipping into—is assuming that anyone who disagrees with you just hasn’t activated their thinking module. That they’re running GPT-4o instead of o3. This, of course, can’t always be the case.

Lastly, like many broad and abstract frameworks, Dual Process Politics may be difficult to falsify. So, do with it what you will.

If you're going to collect your thoughts on dual-process politics into one place, then I’ll also leave the critiques I left on that video and post in one place. Though a lot of it is already touched on/incorporated, so I will use quotes from the article that touch on the critique before I present it. I will organize it into three main sections/critiques.

1) The Dual-Process Model Still Feels Too Simplistic

You write:

> Before proceeding, a quick disclaimer: while Dual Process Theory is highly influential, it’s not uncontested as a framework for psychological decision-making.

I'm happy you started thinking about critiques of dual-process theory but beyond the problem you linked, I have a some more problems with the theory.

The replication crisis hasn’t been kind to DP, and when you look at it closely, it breaks down in ways that aren’t trivial. Take driving or typing: these are clearly intentional actions, but they’re also not fully conscious. If System 1 is "unconscious and automatic" while System 2 is "conscious and deliberate", then where do these fit? If I’m driving somewhere familiar, I’m not consciously thinking about every turn, but I am intentionally driving to my destination. So is this System 1 or System 2? The distinction just doesn’t hold up well under scrutiny.

Then there’s the issue of unconscious influences on conscious thought. Let’s say I’m actively debating which brand of chocolate to buy, weighing my options logically. But in reality, I’ve already been nudged by past advertising, branding, and placement in the store. Is that System 1 or System 2? If we can’t even cleanly separate the two in simple decisions like this, applying it to political thinking feels even messier. There is a problem with nudged/directed *motivated* reasoning.

This is why I suggested before that it might make more sense to frame political thinking as a spectrum—on one end, people who spend a lot of time and resources analyzing policy; on the other end, people who don’t have that luxury. This framing keeps most of the ideas in your model intact while avoiding the pitfalls of an oversimplified duality.

2) A worry about a label for "System 2 thinker"

You write:

> In practice, most people don’t have the time, energy, or inclination to devote significant mental compute to politics.

I'm happy you incorporated that critique of mine into the post, but I do urge you to go further and examine the material conditions that lead some people to not do it. You touch on it, but, at the risk of sounding like a stereotypical socialist, think about the underlying material conditions and class conflict involved.

I worry that if we accept this dual-process framing uncritically, it might lead to the creation of a self-proclaimed ingroup of "System 2 thinkers": people who see themselves as more rational, more deserving of attention, or more politically sophisticated. The problem becomes pretty obvious when you map it onto the actual political/class/economic landscape.

For example: People love to mock mass movements like BLM for lacking well-formed policy proposals, and using slogans like ACAB instead, but step back for a second—why is that? If you live in an overpoliced neighborhood with lead pipes, food deserts, and constant exposure to environmental hazards, you’re not spending much time writing white papers on policy solutions. This is a class of people too busy trying to survive. Meanwhile, the class of people who do have time and resources to craft detailed policy proposals are, more often than not, the ones who are already doing fine under the status quo.

Political analysis costs time and nutrients. Analysis may be objective, but preferences are subjective. If the group that can write analysis prefers blue buildings while the group that can't prefers red buildings, a world that prioritizes the worldview of "system 2 thinkers" will be filled with blue buildings, even if it's mostly or wholly subjective.

If you have to work two jobs to get by, you’re simply not going to have the energy to sit down and write out a political plan to address your needs and preferences. But that doesn’t mean your grievances aren’t real, or that they don’t matter. The danger of an ingroup of "System 2 thinkers" is that it could just end up reinforcing existing inequalities — because the people who already have the time to think deeply about policy will naturally set the terms of the conversation, while those who don’t will be dismissed as reactionary or uninformed.

3) "Far" and "Extreme" are just code for "Threatening to status-quo"

You write:

"There’s also a danger of misinterpreting what this framework tells us. For example, we shouldn’t assume that radical ideas are wrong by default. Some System 2 superusers end up with radical conclusions (I might have some of my own)."

This is the weakest of my critiques, and may not even apply to this post (so skip this one if you're short on time).

I've touched on before, so I'm happy to see it included. Although our previous discussion on this was about the words "far" and "extreme". Maybe you meant "radical" as similar to "far" in that discussion? In any case the point I’ve brought up before (and I still think applies) is that words like "far" and "radical" and "extreme" aren’t used consistently. They’re not neutral descriptions of how different a belief is from the mainstream; they’re mostly just ways of saying "threatening to power structures."

I used the example of anarcho-primitivism. It’s obviously more "extreme" than, say, a standard environmentalist position, but nobody calls anarcho-primitivists "far-left extremists." Why? Because they’re a bunch of niche philosophers with no real power. They’re radical, but not a threat, so they don’t get branded as extremists. On the other hand, if you advocate for something like worker co-ops at scale, suddenly that’s "radical leftism"—even though it’s way less of a departure from the status quo than the anarcho-primitivists.

But again, this last one is more a word of caution for the language of future posts than a substantial critique.

I do like the article -- but here are some questions to eventually draw you to having the exact same (correct /s) views as myself:

1) What is a process?

2) What does it mean for a human to "process"? ("What are you a Mill? Are you grinding Wheat?" - B.F.Skinner)

3) What does it mean for the dual process theory to "approximate reality"? What does that claim actually mean

Then Extension/Joke Questions:

4) Why was the cognitive revolution a mistake?

5) How can behaviourism/operant conditioning explain mice navigating a certain way around a Maze... (lol: "it definitely can't, so now we need "cognitive processing" -- wait, wtf how does that help)

6) Why only two processes? Why not 3, 7, 21?

7) So is it better to live in a system 2 world where we have 7 hour streams on Joe Rogan about whether the Holocaust actually happened because is there really evidence for any of that stuff, or is it better to have the vast majority of people seeing incredibly concerning politics and saying "fuck you fascist" without the need for endless interminable discussion (against the backdrop of Oxford Oak and Hardback books)