Actually, Horseshoe Theory is True

Psychological Horseshoe Theory

1. Horseshoe Theory

Horseshoe theory asserts that the far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite end of the political spectrum, closely resemble each other. It’s a seductive concept, particularly in the world of memes and quick political takes, but it's not exactly held in high regard by serious scholars. Academics point out that the ideological foundations of the extreme left and right are fundamentally different, and their policy goals often diverge sharply. The far-left dreams of dismantling capitalism and building a radically equal society, while the far-right is usually more concerned with maintaining rigid hierarchies or even reverting to some nostalgic past.

But there’s a dimension, distinct from ideology or policy, where evidence that may support a Horseshoe Theory is steadily growing: the psychological dimension.1

2. The Psychological Dimension

A pivotal moment in the formalization of political psychology occurred after World War II, driven by a growing urgency to understand the psychological roots of authoritarianism. The atrocities of Fascism and Nazism left an indelible mark, sparking a need to comprehend how such extreme ideologies could captivate and control entire societies.

Emerging from the crucible of the Frankfurt School, Theodor Adorno was the first to articulate the concept of the authoritarian personality. The idea was to identify a psychological profile largely associated with the far-right. Adorno and his colleagues published papers (and even an entire book) claiming that individuals with this personality type often exhibited traits such as rigid thinking, submissiveness to authority, and hostility toward those perceived as outsiders or non-conformists. However, the statistical methodologies of the 1950s were relatively rudimentary, and the findings, influenced by the bulging field of psychoanalysis, did not always meet the rigorous standards of contemporary research.

Nevertheless, the core idea persisted and evolved. Psychologists and political scientists continued to explore the psychological correlates of authoritarianism, employing a variety of new approaches and methodologies. One of the most significant shifts was the move away from Adorno's psychoanalytic framework toward more empirical and behavioral models. In the 1980s, researchers like Bob Altemeyer developed new theories and measurement tools, such as the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Altemeyer's work was particularly influential because it emphasized specific attitudes and behaviors, rather than the deep-seated personality traits rooted in childhood that Adorno had focused on. This shift allowed for a more nuanced and measurable understanding of authoritarian tendencies.

Around this time, some researchers, albeit gradually and somewhat timidly, began to notice that certain behaviors and attitudes typically linked with right-wing authoritarianism -such as intolerance of dissent, dogmatism, and a strong preference for conformity- could also be found in the more radical factions of left-wing movements. This observation challenged the prevailing notion that authoritarianism was a uniquely right-wing phenomenon.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, this line of inquiry gained traction, leading researchers to develop tools to measure authoritarianism on the left. Left-Wing Authoritarianism (LWA) was conceptualized as a counterpart to Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA), where individuals exhibit authoritarian tendencies within the framework of left-wing ideologies. This measure sought to capture the same psychological rigidity, but applied it to leftist ideals.

While Some scholars expressed doubts concerning the validity and practical relevance of the LWA construct, even likening it to a myth akin to the Loch Ness Monster (Stone, 1980) , others have long contended that left-wing authoritarianism is a significant phenomenon worthy of serious scientific inquiry. The evidence has been recently mounting (Proch et al., 2018; Conway et al., 2018, 2021; Conway and McFarland, 2019; Fasce and Avendaño, 2020).

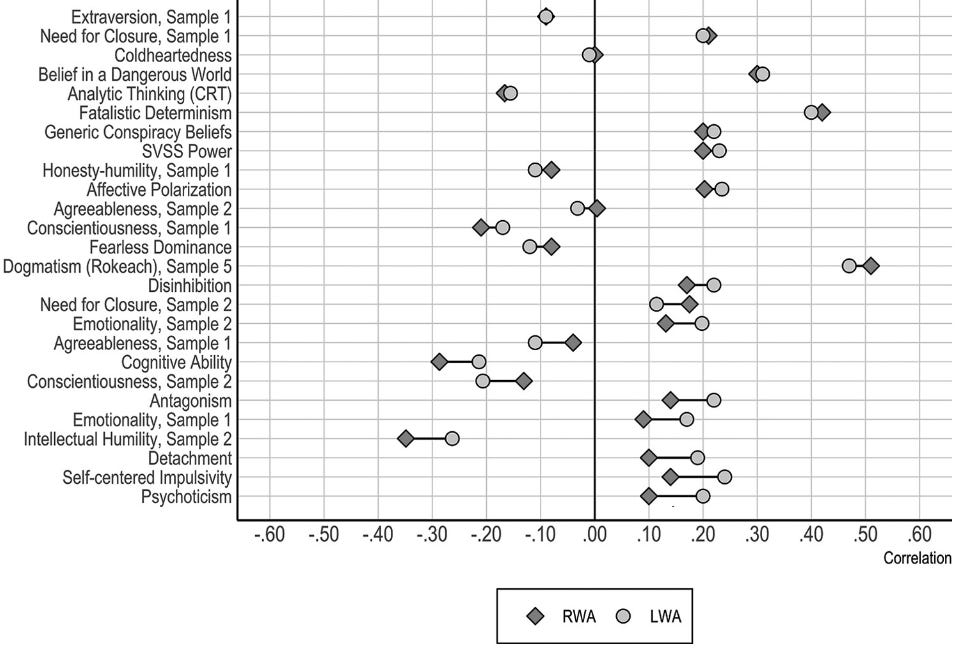

In 2021, Thomas Costello, a researcher at MIT specializing in the study of authoritarian personalities, published -along with his coauthors- one of the latest iteration of this research delivering one of the most comprehensive studies to date. His work, that employed rigorous statistical methodologies, was titled Clarifying the Structure and Nature of Left-Wing Authoritarianism.

The results were stunning.

LWA and RWA demonstrated virtually identical relations with numerous variables. While some psychological differences between the two constructs were identified, the overwhelming finding was the dominance of their similarities, as the authors noted:

LWA and RWA seem to reflect a shared constellation of traits that might be considered the “heart” of authoritarianism. These traits include preference for social uniformity, prejudice toward different others, willingness to wield group authority to coerce behavior, cognitive rigidity, aggression and punitiveness toward perceived enemies, outsized concern for hierarchy, and moral absolutism.

In 2023 another study corroborated the tendencies for authoritarianism to be found on both the extreme right and left.

Far from standing alone, the research on the authoritarian personality is not the only one to arrive at horshoetheoriesque conclusions. In fact, there are so many other papers to cite that, to keep this article from turning into a novel, I'll just rapid-fire some at you.

Decreased integrative complexity (more black-and-white thinking) was observed among the more extreme members of the British House of Commons, both on the left and right, compared to political moderates (Tetlock, 1984).

Political extremists have also been found to form more sharply distinguished homogenous clusters of similar versus dissimilar stimuli, suggesting that they perceive the social world in simpler and more clearly defined mental categories (Lammers, Koch, Conway, & Brandt, 2017).

Both political extremes tend to believe that solutions to crises are straightforward, while moderates are more likely to see them as complex and nuanced (van Prooijen, Krouwel, & Emmer, 2018).

Political extremes believe conspiracy theories more strongly than moderates (van Prooijen, Krouwel, & Pollet, 2015).

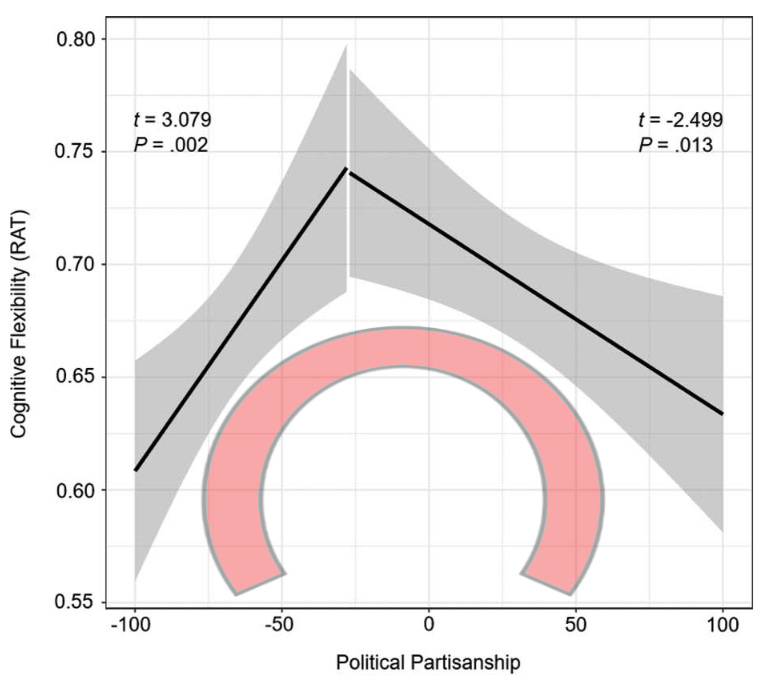

Partisan extremity was found to be related to lower levels of cognitive flexibility, regardless of political orientation (Zmigrod et al. 2019).

Political extremes exhibit overconfidence in their political and non political beliefs (Toner, Leary, Asher, & Jongman-Sereno, 2013, Brandt, Evans, & Crawford, 2015).

In a large Dutch sample, participants on both extremes belittled out-groups more strongly than did politically moderate participants (van Prooijen et al., 2015).

Individuals with radical beliefs displayed less insight into the correctness of their choices and showed a generic resistance to recognizing and revising incorrect beliefs when presented with post-decision evidence, while moderates had better meta-cognitive abilities (Max Rollwage et al. 2018) .

Extremists —both on the left and right of the spectrum—experience greater psychological distress about their economic future (van Prooijen, Krouwel, Boiten, & Eendebak, 2015).

Some of these findings seem to go together: people on both extremes tend to struggle with analytic thinking, cognitive flexibility, and meta-cognitive abilities. They score high on dogmatism and are more likely to buy into conspiracy theories.

In other words, what we’re seeing is mounting evidence for a kind of psychological horseshoe theory, where the far-left and far-right may be closer in mindset than they’d care to admit.

3. Dual Process Politics?

2Alright, in this section we will speculate as to what is going on, so buckle up for some lower epistemic accuracy.

Some of the findings aren’t particularly shocking -like the fact that extremists report higher levels of psychological distress or that they tend to belittle the outgroup more than moderates. The real concern comes when you look at the levels of dogmatism, cognitive rigidity, and the troubles with analytic thinking. It’s not just that extremists feel strongly; it’s that they struggle to think critically about their own beliefs. Their psychological profile doesn’t just attract extremism -it may actively prevent them from escaping it.

What’s happening may be explained by the fact that radical ideologues are relying on their System 1 processes for forming beliefs about the world.

If you’re not familiar with a System 1 process, don't worry -it comes from Dual-Process Theory. Dual-Process theory posits that human cognition operates on two systems: System 1, which is fast, automatic, and provides quick heuristics, and System 2, which is slower, more deliberate, and analytical. System 1 excels at tasks that are familiar and routine, where quick decisions are required while System 2 shines when dealing with complex, non-routine tasks that require careful analytical thought.

Given that Dual-Process Theory broadly applies across many domains of thought -since it deals with thought in general- it wouldn't be surprising to find its dichotomy at work in politics as well.

If extremists were indeed relying on their System 1 processes instead of engaging in analytical thinking to navigate the complex and multifaceted domain of politics, we would expect them to engage in more black-and-white thinking, be more dogmatic, believe that solutions to crises are straightforward, and embrace all sorts of conspiratorial though -along with a host of other correlates found in the referenced research.3

We would also expect them to be wrong more often than more moderate individuals.

Interestingly, this could help explain why authoritarian countries like Russia, China, Venezuela, Iran, and North Korea can bond together despite their differing ideologies. Perhaps it’s not about what they believe -it’s about how their leaders think.

This perspective also helps to explain why the elites in Nazi Germany were rife with esoteric, pseudo-scientific and conspiratorial views, such as the Jewish conspiracy or the bizarre World Ice Theory, which posited that ice was the fundamental substance of all cosmic processes and had shaped the entire development of the universe -yes, you read that correctly. Apparently Himmler himself believed this stuff.

Or take Stalin, who bought into Lysenkoism, a pseudoscientific theory that crops could be "educated" to grow in harsh conditions, conveniently aligning with the Marxist idea that the environment shapes individuals. Numerous scientists who disagreed with this “theory” were executed. Stalin also believed in the infamous Doctors' Plot, a conspiracy theory that Jewish doctors were planning to assassinate Soviet leaders, leading to the arrest and torture of several doctors.

When you look at it through these psychological lens, it becomes less surprising that someone like Mussolini could shift from being a socialist to becoming a fascist. It also highlights just how deeply warped the worldviews of Nazi, Fascist, and Soviet elites truly were. They weren’t just using conspiracy theories as tools -they actually believed in them, which is both terrifying and illuminating.

My suspicion is that the two extremes of the political spectrum feed off each other -the people screaming “ACAB” at the top of their lungs reinforce the ranks of those shouting “QANON”, and vice versa. Russia evidently agrees, as their propaganda efforts aim to amplify both extremes, intensifying the polarization that benefits their agenda.

At this point, it's important to clarify a possible misconception: if a psychological version of horseshoe theory were indeed accurate, it wouldn't imply that the extreme left and right are identical in every way, nor would it suggest that their supporters are equally numerous. One pole can easily outweigh the other.

It’s entirely possible -and indeed plausible- that different extremes pose greater risks in different countries, depending on the specific social, historical, and cultural context.

For instance, in America, one political party seems far more enthralled by extremism, cognitive rigidity, and conspiratorial thinking than the other -but I’ll leave it to the reader to decipher this complex enigma.

In fairness we will show evidence for the the fact that political extremes share similar traits but we will not talk about the curvature of the horseshoe.

This could also explain why young people, who may not have yet deeply explored or reflected on political issues, tend to hold more extreme views.

I can't remember what it's called but there's an astral codex 10 post about how socially acceptable an idea is affects what kind of people believe it. When being gay was taboo for example, the average pro-legalising-homosexuality advocate would have been a really unusual and probably quite deplorable person. Now that being gay isn't taboo the average person with pro-legalising-homosexuality views is almost the same as the average person.

I'd say I'm far-left and being honest I'm probably also more sympathetic to far-right ideologies than the average person. But I still think horseshoe-authoritarian-psychology-theory is wrong just because the connection between being fascist and communist in liberal society is probably just having a tendency to go against the social norm. In a fascist society I'd probably be more pro-communist and more pro-liberal than average. In a communist society I'd probably be more pro-fascist and more pro-liberal than average. I don't think there's any inherent connection.

Hope that's a helpful perspective.

edit: here's the SSC post: https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/02/04/respectability-cascades/

Hmmm, I think this is more due to how the words "far" and "extreme" get interpreted in these studies. Take a belief like anarcho-primitivism. Clearly this a more "far" or "extreme" version of regular left wing hippies, but they are not authoritarians, and it's mostly eccentric philosophers that advocate for this view. Even though that worldview is far left of the regular left wing (more extreme) we don't think of them as leftwing extremists. It almost becomes a tautology, "far" and "extreme" in horseshoe theory do not mean far from the mainstream, it means "prone to authoritarianism", so exclusively Stalinists etc. When we measure these "far" and "extreme" leftists we find that... they are prone to authoritarianism...wow.

I say this because a lot of people who vote for "non-extreme" candidates might have extreme views. For example, I mostly vote for social democrat types, but I would also want to create and join a hive-mind. This belief is much more far/extreme than a MAGA person wanting Trump to become a dictator, dictators are aplenty in the world, yet I'm not considered "extreme".

Or from the other side, a lot of people in the tech blogosphere vote for mostly neoliberal types but also want to create and be ruled over by a benevolent all powerful AI. This is much more extreme than leftists wanting to replace all for-profit companies with worker coops, but they're not considered "extreme". I think the moniker of "far" or "extreme" just gets put on people who are authoritarian and not on people like me or the anarcho-primitivists (who are actually extreme) because we're not a threat. The word is closer to an imputation than a description.