1. The Fundamental Problem of Norm Adoption.

A civilization can be understood as a complex and organized human society characterized by various elements such as social, cultural, economic, and political structures. Norms, which are shared rules and expectations that guide behavior within a society, are integral to establishing order and stability within a civilization.

But where do norms come from?

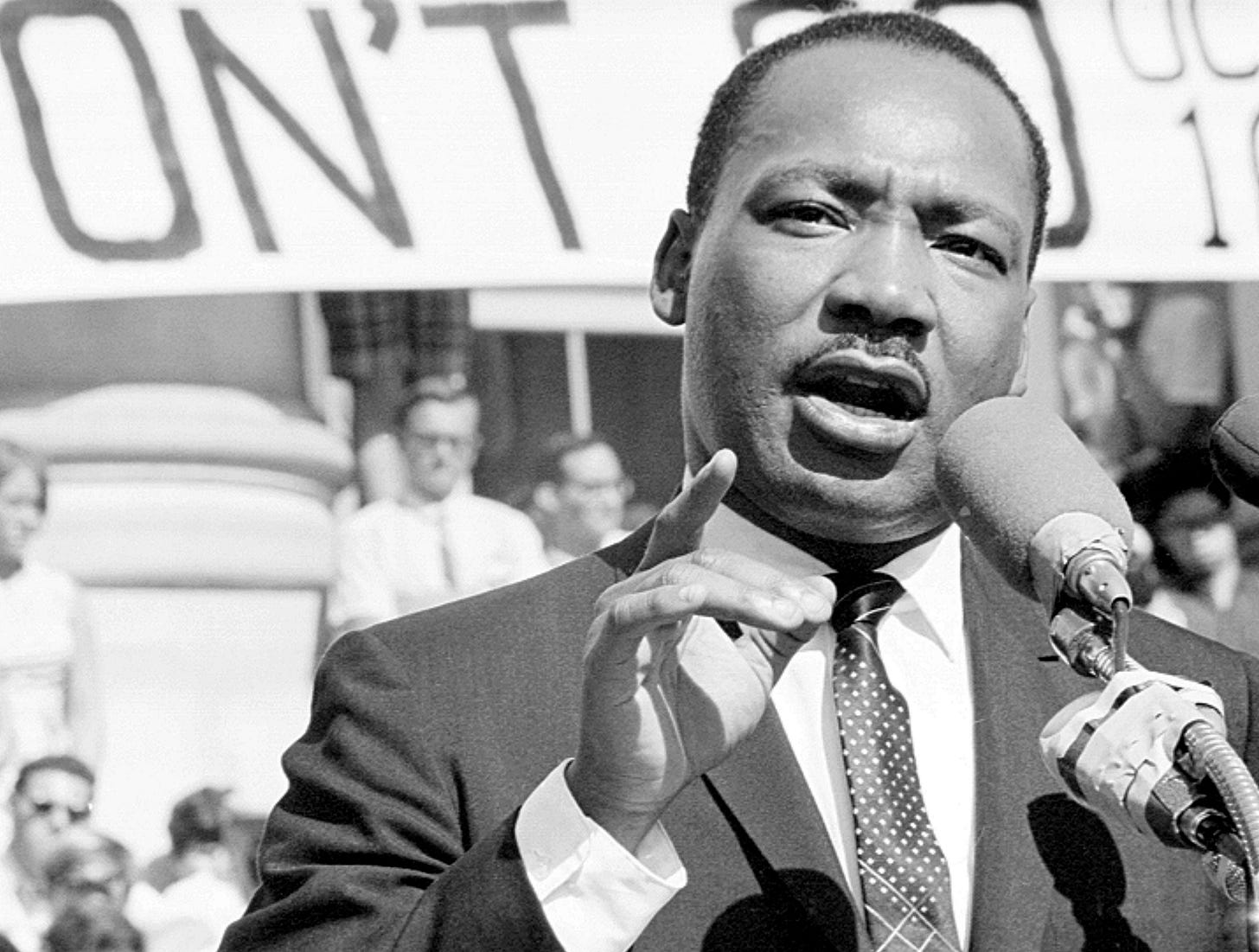

Well, norms come from people. A norm entrepreneur takes deliberate actions to change existing social norms or create new ones, within a given society or community, desiring that his ideas find resonance and widespread acceptance among his fellow humans. Norm entrepreneurs actively ponder how to improve society and seek to introduce new ideas, values, or practices that work towards such a goal. We all know some famous norm entrepreneurs: Martin Luther King, Karl Marx, Jesus Christ, but not all norm entrepreneurs are remembered; the names of the pioneering norm entrepreneurs who propelled humanity from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a settled agricultural society have been lost to the passage of time.

The ultimate goal of a norm entrepreneur is to achieve widespread and pervasive adoption of their proposed norms thereby cementing them as a societal standard. This happens through what academics call a norm cascade—or, as the cool kids would say, “going viral.”

A norm cascade refers to a phenomenon where a new social norm rapidly spreads and becomes widely utilized within a society. It occurs when individuals observe others adopting a particular behavior or belief, leading them to conform to the same norm themselves. As more people conform, the norm gains momentum and reaches a tipping point, eventually becoming the prevailing social expectation.

Once a norm achieves widespread adoption, it gradually becomes internalized, embedding itself into individuals’ behavior as second nature. Internalized norms guide actions effortlessly, without the need for external enforcement or constant oversight. At this point, the norm entrepreneur can sit back, dust off their hands, and declare, “Mission accomplished.”Or at least, they can until the next norm entrepreneur comes along to shake things up again.

While a norm cascade can occasionally occur organically, it is usually a challenging and demanding process that requires dedicated effort and perseverance. To gain widespread acceptance, a new norm must pass through the judgment of a diverse society, where individuals range in expertise and perspective. Moreover, the majority of society lacks the time to engage in a slow and meticulous reflection (System 2 thinking) necessary to rationally evaluate whether the societal changes proposed would be beneficial.

So the norm entrepreneur is caught in a bind. On the one hand, he’s got a grand idea—a tweak to the social machinery that he’s sure will make the world a better place. On the other hand, he’s stuck with the unenviable task of persuading a lot of people to adopt it. Most of these people are busy, distracted, and short on the kind of time or resources needed for slow, careful deliberation about whether his proposed tweak is actually a good idea. Even if the entrepreneur is absolutely convinced that his new norm will make society happier, richer, or better in some other tangible way, none of that matters unless he can get everyone else on board. And if he can’t? Well, then his great idea dies on the vine. Let’s call this the fundamental problem of norm adoption.

2. Overcoming the problem

It’s not immediately obvious how norm entrepreneurs navigate the fundamental problem of norm adoption. Occasionally, the issue resolves itself when a new norm is so intuitive and self-evidently valuable that it gains traction almost effortlessly. However, this is the exception rather than the rule. More often than not new norms are resisted. People don’t usually like change, let alone societal change.

Confronted with the fundamental problem of norm adoption, norm entrepreneurs must often think creatively. One potential solution is to enforce the new norm directly, leveraging a position of power or influence within society. However, this approach is far from foolproof. Imposing a norm can provoke resistance, leading to protests or pushback that may slow down—or even derail—the process of internalization. Simply put, while enforcement can jump-start norm adoption, it doesn’t guarantee lasting acceptance.

There is, though, another way out of the impasse created by the fundamental problem of norm adoption: manipulation. Rationality is expensive. It demands time, energy, and cognitive resources, which is why we use it sparingly. Instead, our minds rely on intuitions—quick, efficient heuristics that help us navigate the world. These snap judgments often serve us well but are far from perfect, frequently influenced by biases and mental shortcuts.1

Norm entrepreneurs might be tempted to appeal directly to these intuitions rather than engaging the rational faculties of their audience. By subtly leveraging the cognitive biases and mental shortcuts people rely on, they can nudge society toward change with a touch of friendly manipulation. From their perspective, this might even seem like the most virtuous path: gently steering people toward better outcomes that ultimately serve their interests. A small lie for the greater good.

But surely this paints the (mostly) well-intentioned norm entrepreneurs in an unfair light. The solution to the fundamental problem of norm adoption—and by extension, the key to the evolution of civilization—couldn’t possibly rest on a continuous exploit.

Did you know that all human civilizations ever discovered had a religion? Religion is purported to be a so-called, human universal; a feature of humanity for which there is no known exception. In fact, it is often suggested that religion is adaptive, with some proposing that civilizations lacking it struggle to survive and quickly fade away.

The purpose of religion has long been debated among scholars. Some argue it served to foster social cohesion, while others suggest that belief in the supernatural helped early humans make sense of their environment, explain natural phenomena, and cope with existential questions.

But if we allow ourselves a moment of mischievous speculation, another possibility emerges. Religion may have provided a remarkably convenient mechanism to exploit human cognitive biases, furnishing a potential solution to the fundamental problem of norm adoption. By persuading people that a powerful deity has decreed certain norms as just—and that the norm entrepreneur is merely the messenger—a seamless norm cascade could be achieved, neatly sidestepping the need for rational deliberation. If a norm entrepreneur sought to update existing norms, they could simply claim that previous divine messages had been slightly misinterpreted. A new, divinely inspired text could appear (to then be appended to the old one). No need for the inefficiency of wandering around, trying to rationally persuade others. God said so! (in mysterious ways).2

At this point it’s fair to wonder if we’re being overly suspicious of our well-meaning norm entrepreneurs. Surely, we wouldn’t want to think ill of them—after all, it’s common knowledge that politicians and high-ranking clergy never lie. Yet, as Giulio Andreotti, the 41st Prime Minister of Italy and a norm entrepreneur in his own right, famously remarked, “It’s a sin to think badly of someone, but you’ll often be right.”

3. Implications

Today, we wield tools of unprecedented power to bypass rationality. Through the advent of mass communication, digital ecosystems, and algorithmic persuasion, dissenting norm entrepreneurs wield unprecedented influence over human intuitions, carving deep epistemic divides across society.

It’s no wonder so many feel deceived and manipulated by unseen forces—because, in many ways, they are. This is the essence of politics: what cannot be achieved through rational discourse is pursued by other means. Yet, what is usually missing in the popular conception of the phenomenon is that there appears to be no great alternatives and that, in many cases, the people who try to influence you have the well-being of society in mind. You’re being manipulated for the perceived greater good.

In a democracy, the ideal is that competing norm entrepreneurs balance each other out, leaving the more rational segment of society to steer the ship. But as we become more adept at appealing to instincts, politics risks devolving into a pure power struggle—where the victor is simply whoever commands the most resources to sway the most minds.

Will the future unveil a better answer to the fundamental problem of norm adoption?One thing seems assured, until the day when we collectively evolve into more adept rational agents, our existence appears shackled to our current solution.

Epistemic confidence: 70% Fun while writing: High

This aligns with the prevailing understanding of our cognition, as supported by the latest research and insights in the field (see Thinking, Fast and Slow by Kahneman for an introduction).

Perhaps groups of humans who didn’t adopt this mechanism could never consolidate their society enough for it not to die.