Avoid Absolutizing the Oppressor-Oppressed Distinction

It can lead astray.

1. Power: the Academic Introduction

After World War 2, the world witnessed the devastating consequences of unchecked power. Therefore, it may not be surprising that throughout the postmodern era, the concept of power became a focal point for scholars and thinkers, emerging as a central theme for exploration and analysis.

Chomsky critiqued how power is wielded by institutions, such as governments and corporations, to influence public opinion and maintain control over the general public. His "propaganda model" of media, developed with Edward S. Herman, suggests that mainstream media often serves as a tool for the interests of the elites, disseminating information that aligns with their agenda. Moreover, Chomsky described his personal political stance, anarchism, as the doctrine advocating for the dismantling of illegitimate power structures -a truism, as he likes to put it.

Foucault, by contrast, viewed power as woven into every aspect of society, permeating all levels and relationships. His analysis zeroed in on disciplinary mechanisms embedded in institutions like schools, prisons, and hospitals, and on how power is intertwined with knowledge itself. According to Foucault, power is exercised not just by governments but through the very language we use to understand the world. In general, postmodern thinkers developed a critical view of power bringing attention to the experiences and viewpoints of those historically excluded or marginalized.

But in these writings, we won’t get too tangled up in the dense academic theories of power, the kind hashed out in endless papers and symposiums.

Instead, we’re going to explore a specific way some people tend to think about power—a perspective I’m all too familiar with because it’s exactly how I used to think about it.

2. The Public (Mis)Perception

I’m not sure the nuanced ideas about power discussed in academia ever really made it into the public consciousness. If anything, they might have added fuel to the fire of a general distrust—if not outright hatred—of power, a sentiment that already seems to smolder quietly in the background for most people.

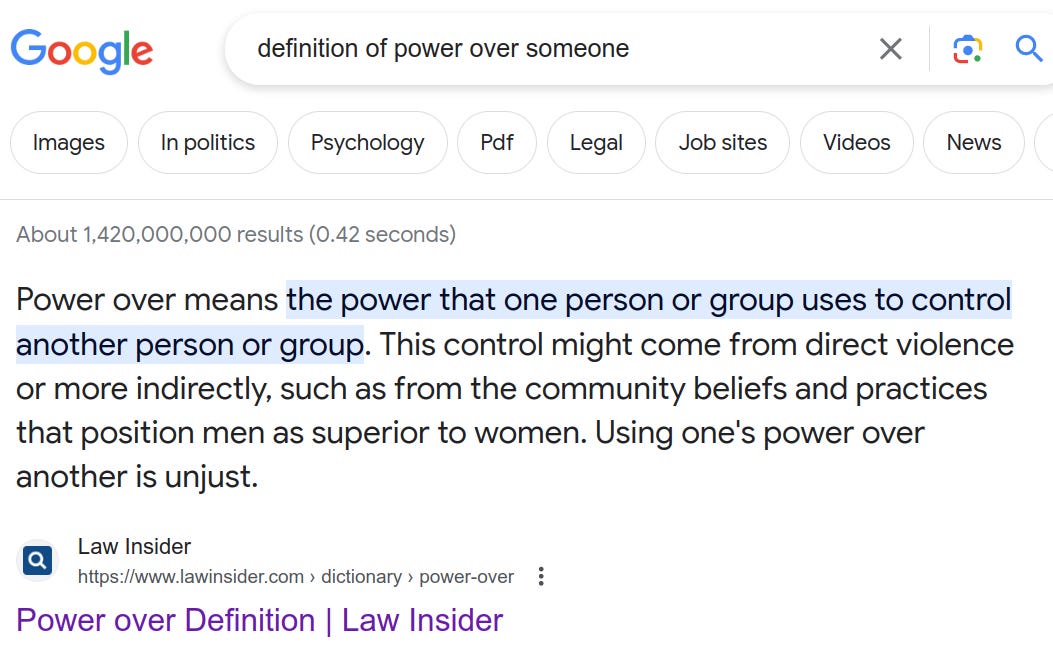

The other day, I was Googling “definition of power over someone.” I wasn’t expecting anything groundbreaking, just a quick refresher. Instead, I got hit with a definition that left me staring at the screen like, “Wait, that’s what we’re running with now?”

The following, I thought to myself, was clearly mistaken.

“Using one’s power over another is unjust.”

This brought back memories of how my progressive friend and my past self thought about power—as this vague, ominous force that was inherently bad; ontologically evil.

The truth is that there are plenty of cases where using one’s power over another is far from unjust: it’s the right thing to do.1

Consider parents: they possess a unique authority to shape and influence their children’s behavior in profound ways. This power manifests in two primary forms: soft power, which relies on persuasion, emotional connection, and modeling to guide preferences, and hard power, grounded in financial control and legal authority to make decisions on their children’s behalf. To fulfill their role effectively, parents should wield both forms of power—soft and hard—balancing encouragement and attraction with the occasional need for disciplinary measures, such as punishment, as a tool for guidance. Parents who avoid using their influence often struggle to provide the structure and direction essential for healthy development, creating a vacuum that can harm the child’s growth. When raising kids, exercising power isn’t an overreach—it’s a moral responsibility.

But if that knockdown example didn’t convince you, let’s consider another: isolating violent murderers from society. When the judicial system imprisons murderers, the state is exercising its power to forcibly detain individuals. Far from being an abuse of authority, this is a just use of power aimed at protecting innocent citizens and, ideally, rehabilitating the offender.

So, why do so many people come to perceive the exercise of power as inherently negative, to the extent that this feature is embedded in some definitions?

One explanation stems from a misinterpretation of the historical critiques of power and authority, beginning with the Enlightenment. Thinkers like Rousseau, Locke, and Voltaire challenged traditional power structures, emphasizing the importance of legitimacy, the consent of the governed, and the need to constrain rulers. Their critiques laid the groundwork for a more skeptical view of authority, one that has profoundly influenced modern thinking.

In the 19th century, this skepticism evolved further with the introduction of the oppressor-oppressed distinction, popularized by Marx (and, depending on your interpretation, Hegel). This framework highlighted social dynamics where one group—the oppressor—actively coerces, excludes, or controls another—the oppressed—resulting in their suffering and disadvantage. It became a powerful lens for analyzing systems of dominance, such as race, gender, and class, revealing how power could perpetuate inequality and injustice.

While this framework offered critical insights that helped society improve, it also came with unintended consequences. The continuous focus on the darker sides of power may have led to a broader cultural association of power itself as being absolutely negative. This misinterpretation risks overlooking the fact that power, when used responsibly, can be a force for protection, progress, and justice. It’s not power itself that is the problem, but its misuse—a distinction that early thinkers likely understood.

To highlight just how slippery and easy to misinterpret these concepts can be, I pulled a small trick in the previous paragraphs. I slipped in a flawed definition of ‘oppressor’—one that captures how some people erroneously think about it—and I’m betting most didn’t catch the mistake right away.

To be labeled an oppressor, it’s a necessary condition to actively coerce, exclude, or control another group, leading to their suffering or disadvantage, but it’s not a sufficient one. In fact, teachers who grade students are not oppressors even though their grading will exclude some of them from being accepted by top schools, leading to their disadvantage. The judicial branch is not an oppressor when it coerces perpetrators away from the larger society, leading to their suffering or disadvantage. A bystander who is a black belt in jujutsu is not an oppressor when he uses his physical power to wrestle and control an active shooter to the ground, leading to his suffering or disadvantage.

To salvage the previous definition of oppressor we need to add some normative language to it.

Oppressor: An oppressor is a person, group, institution, or system that unjustly exercises power over others. They use their position or authority to coerce, exclude, or control individuals or groups, leading to their unjust suffering or disadvantage.

What occasionally seems to happens is that some people remove the normative language from the definition of “oppressor,” turning the oppressor-oppressed distinction into a moral framework of its own—one where the powerful are automatically cast as evil. This leads to an “oppressor-oppressed morality,” where the rightness or wrongness of actions is seemingly judged solely through this one-dimensional lens. The result is a distorted, oversimplified moral landscape that ignores nuance and complexity.2

3. The Oppressor-Oppressed “Moral Theory”

To better understand the informal oppressor-oppressed morality that I believe many might reflexively adopt, we need to delve into its foundations—a challenging task for an unwritten moral framework. I propose that its essence rests on two flawed dogmas. The first is:

a. The powerful is always the oppressor and the weak is always the oppressed.

The examples we have previously explored already show us why this is wrong. In many cases, parents aren't malevolent oppressors, nor is the judicial branch of government. But one can conjure up even more decisive cases: those where the weak is the oppressor and the powerful is the oppressed.

Consider a teenage individual from a disadvantaged ethnicity, hailing from a financially challenged family, who consistently bullies an affluent, physically imposing white male. The white male tries to ignore him, turning the other cheek, hoping the verbal harassment will cease, yet it persists, causing him considerable distress and anxiety. In this scenario, the powerful is being oppressed by a person who has less power than himself.3

Certainly, these cases are exceptional. Typically, the powerful are more prone to being oppressors than the weak. Nevertheless, they show that the powerful isn't always the oppressor, leading us to discuss the second erroneous tenet of the oppressor-oppressed morality:

b. The oppressed can do no wrong, the oppressor can do no right.

Sometimes, you’ll hear this principle expressed as: the oppressed have the right to fight the oppressor by any means necessary. Again, we are facing a moral confusion. Consider an employee who is pushed to work long hours against the terms of his contract by a demanding boss. By most accounts, he is oppressed by someone more powerful than himself. But if, one night, in a fit of retaliation, the employee drew a pistol and shot the boss dead, he would not have performed a moral action. The oppressed does not have carte blanche to inflict whatever suffering he pleases on the oppressor.

Similarly, consider the oppressive employer: his actions at work are morally wrong. But if, after hours, he volunteers at a charity, this act would be morally commendable on its own—it doesn’t modify or justify the oppression he perpetuates, but it’s still a good deed in its own right.

This discussion segways into a hard to stomach truth: sometimes the path towards a better society involves appealing to the oppressor’s humanity. Take the civil rights movement: a movement that, at its heart, was about showing the oppressor their own reflection and asking, 'Are you really okay with this?' History shows us this approach works—people realized they were hurting others, whether Black Americans, gay people, or any marginalized group, and some of them changed.

Now imagine if the civil rights movement had taken a different route. Suppose it had been defined by bombings or violent uprisings. Sure, it might have gotten headlines, but would it have brought about equal rights? Not likely. It would have probably brought more suffering and deepened divisions, without much progress. It would have been the morally wrong thing to do. Instead, the movement took the harder path: insisting on dignity and nonviolence, asking our society to recognize its own humanity. And as slow and frustrating as that approach can be, it’s hard to argue with the results.

4. Overcoming the Dogmas

What often happens is that the oppressor-oppressed distinction, instead of serving as a useful heuristic—that those with power, given their greater responsibilities and potential to oppress, deserve closer moral scrutiny, while those with less power require protection—hardens into a rigid moral dogma: the powerful are inherently oppressors and therefore morally wrong, while the weak are automatically oppressed and thus morally right. The logical outcome of the two fallacious principles of the oppressor-oppressed morality leads us back to the first result of my Google search: exercising power is always unjust.

Perhaps it is in part due to this mistake that many postmodernists argued that the state (the powerful) should not deny children under the age of 15 (the oppressed) the right to consent to sexual relations. Or why some believe that America (the most powerful country) can’t engage in foreign policy without being the oppressor -a stance humorously referred to online as 'America bad'.

It's common for our minds to simplify helpful heuristics into rigid, black-and-white rules to conserve cognitive resources (a form of system 1 thinking). Consequently, it’s no wonder that the oppressor-oppressed distinction, with all its moral shades, often gets misinterpreted, fueling the kind of power-phobia we’ve been talking about. But power itself isn’t inherently good or bad. Power is just a tool, something that can be wielded for better or worse. Ideally, it should be entrusted to those with benevolent intentions and a dose of rationality.

Sure, there are issues. Too often, the powerful dodge accountability, sidestepping the consequences of their actions while the powerless bear burdens they didn’t create. And power and responsibility don’t always go together—think trust-fund heirs or influencers with millions of followers but no accountability. The powerful can also fall in love with their own decisions, forgetting that real good usually demands restraint.

Yet, power itself shouldn’t be demonized outright. Sure, it takes intelligence and moral integrity to wield responsibly, but avoiding it altogether risks something even worse: that we start uncritically glorifying weakness as a moral virtue simply because it stands as power’s polar opposite.

We will be working with the following, widely accepted, definition of power

Power: Power is the ability or capacity of an individual, group, or entity to influence or control the behavior, actions, or decisions of others.

I believe that the reason for the existence of this oppressor-oppressed morality comes from a technical problem concerning postmodern moral relativists and normative nihilists. They would like to be able to talk in objective moral terms but can’t, so to get around this problem they use ‘moralized words’, like oppressors, that have a negative connotation baked into them. This language trick betrays the need humans have for normative language and ironically constructs a moral framework that is far from nihilist or relativist.

At least, as physicists would say, when considering the two subjects in a vacuum.